Hello Everyone!

Welcome back to another blog post! Hope you all are having a splendid New Year! Today, I want to talk about a genetic trait that is one of the most common in the human race: colour blindness. With 1 in 12 men and 1 in 200 women being colour blind, it’s extremely prevalent.

What inspired this post, you may ask? Well, since the condition is so common, I personally know a couple of people with it. One of them is my Kaka (father’s brother in Gujarati – in my case, my father’s cousin brother) and my friend from school, Aahan. I wanted to share their stories about dealing with color blindness, the challenges they face, and those they might encounter in the future. So without further ado, let’s get started!

What is colour blindness? Does it mean a person can only see black and white? Or nothing at all? And why is it a genetic trait?

Colour blindness affects a person’s ability to see or differentiate along the red-green or blue-yellow axis of colours, or in rare cases, both. Let’s take my friend Aahan, for example. He has green colour blindness, meaning he struggles to differentiate between shades of green. Light green and dark green, yes, but colours like forest green or swamp green? A complete mystery to him. (And a source of constant teasing for my classmates).

My Kaka, in a rare case, has colour blindness along both axes. For example, he can’t distinguish the colours on a traffic signal and instead sees them all as shades of red.

Colour blindness also exists in varying degrees. Some people are more affected than others. My Kaka, for example, has a more significant degree of colour blindness, while Aahan’s is less in comparison. This condition, however, is not a major hindrance in their daily lives – they live just like you and me. However, it can affect certain job opportunities. For instance, both Aahan and my Kaka cannot pursue careers as surgeons or electricians, as these jobs require precision based on colour. Other professions where colour blindness can pose challenges include driving, cooking, and certain scientific roles.

Why is colour blindness genetic?

The inheritance of red-green colour blindness is linked to the X chromosome. Here’s how it works:

A male baby:

- Will have red-green colour blindness if his mother has the condition since she would pass on the affected X chromosome.

- Has a 50% chance of being colour blind if his mother is a carrier, as she has one affected X chromosome and one normal X chromosome, giving a 50:50 chance of passing on the mutation.

- Will not inherit red-green colour blindness if only his father has it, since the father passes a Y chromosome to sons, which doesn’t carry the gene for this condition.

A female baby:

- Will be colour blind only if both parents have the condition, as she would need two affected X chromosomes (one from each parent).

- Will be a carrier if her father has the condition and her mother doesn’t, since she would inherit the affected X chromosome from her father but a normal one from her mother.

- Has a 50% chance of being colour blind and a 50% chance of being a carrier if her father has the condition and her mother is a carrier, as she could inherit either the affected or the normal X chromosome from her mother.

Other causes of colour blindness can include genetic mutations due to diseases like diabetes or multiple sclerosis.

Is there a treatment for colour blindness? How do you know you have it?

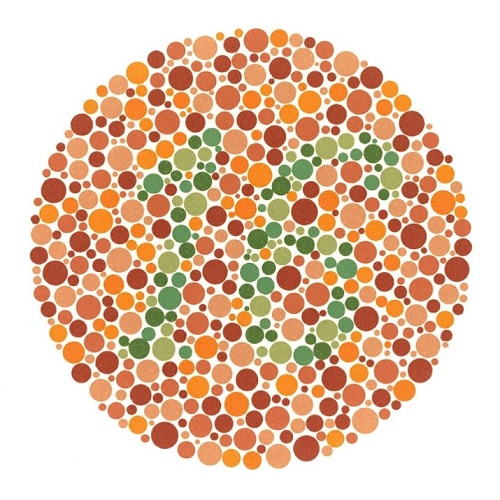

Unfortunately, there is no cure for colour blindness. However, colour blindness glasses exist! These glasses help enhance the contrast between colours, making it easier for those affected to distinguish between them. The way to test for colourblindness is through the Ishihara test. It is a widely used method by eye care professionals to detect red-green colour blindness. During the test, you are shown several plates filled with small, coloured dots. Within these dots, a number or shape is hidden. Your task is to identify what you see on each plate. Some plates display numbers visible only to those with normal colour vision, while others reveal numbers seen only by individuals with colour vision deficiency. This helps determine if a person has difficulty distinguishing between red and green shades.

Next up, I’m sharing an interview with my friend Aahan Prajapati, who also studies in the 11th grade at Adani International School. He has kindly agreed to tolerate my questions so I can share his story with you all!

Question: Hi Aahan! The first question I would like to ask is when and how you found out about your colour blindness. What was your reaction?

Answer: Hello! I found out I was colourblind in 4th grade, but it didn’t come as much of a surprise. My family had already noticed I had difficulty differentiating colours, especially during art classes when I struggled to pick out the right shades. I was officially tested and diagnosed by an ophthalmologist. I wasn’t disappointed by the diagnosis since it hadn’t caused major issues in my life up to that point. My grandfather had the same condition and my family noticed the similarities. However, he hadn’t realized it until he was well established in his career because it wasn’t a significant challenge in his daily life. Although it hasn’t been a major obstacle, I became more aware of its implications once I officially knew I was colour blind.

Question: What challenges have you faced up until now due to your colour blindness, and what is/was the toughest challenge?

Answer: Academically, my colour blindness only caused a few challenges. I lost some marks in exams for using the wrong collars in diagrams, and my art teacher even scolded me once for choosing incorrect colours (she didn’t know I was colourblind at the time). In chemistry labs, flame tests and pH color changes were tricky to figure out, and I sometimes struggled with colour puzzles like the Rubik’s Cube (I am an avid puzzle solver), where colour recognition is important. Outside academics, it occasionally affects choosing clothes or distinguishing between traffic lights, green grass, and dry grass. However, the toughest part has definitely been academics, especially in biology and chemistry labs. Otherwise, it hasn’t really bothered me much.

Question: How do you think your colour blindness will affect you in the future? Or do you think it will affect you at all? Does this affect your career path or not?

Answer: My colour blindness could have influenced my career path later on if I did not know about it, especially in fields where precise colour differentiation is critical, like surgery or becoming a pilot, or electrical engineering. Surgery was the most relevant for me. The Government (Indian government) does not stop me from pursuing it, but I realised it would be more challenging due to my condition. It wasn’t just a technical issue—it also felt like an ethical concern, and I didn’t want to take that risk. It would eventually make me feel under confident about my skills, which would affect me mentally. In the current career path I want to pursue, it would only affect me occasionally, but overall, it doesn’t seem to be a major obstacle.

Question: You also run colour blindness camps for children. Is it because you are colour blind or is there another reason as to why you run it and are so passionate about it?

Answer: Knowing I was colourblind definitely shaped how I see my future. If I hadn’t found out early, I might have taken my career path in a different direction without considering how it could affect me. Being aware helped me understand that it wasn’t my fault when I made mistakes in exams or practical work due to colour confusion. I wanted to make sure other children knew about this as well and did not blame themselves for the mistakes that were out of their hands. For example, just today, a girl discovered she was colourblind because of a test I shared. It made me realise how important awareness is, especially since people can still face job rejections due to colour blindness.

Well, that is all for today! Thank you so much for tuning into another post and I really hope you gained further insight, or learned about colour blindness!

Until next time-

Namaste!